Chicano Border Activists Pass the Torch to Dallas Students

On March 10, Shellie Ross, executive director of the Wesley-Rankin Community Center, took a busload of West Dallas youths, some of them children of undocumented immigrants, to the U.S.-Mexico border in South Texas. The purpose of the trip was to educate the students about Mexican-American history and introduce them to activists in the Chicano movement. This was a month before news and images broke of immigrant children being separated from their parents as part of President Donald Trump's "zero tolerance" program on illegal border crossing. Photographer Hannah Ridings traveled with the group and captured images of the Dallas kids' trip to the border and their meetings with activists.

The brakes shake the bus back and forth as a white SUV pulls onto the road ahead, blocking its way. A tinted window on the Border Patrol SUV rolls down, revealing a face behind mirrored sunglasses and a hand motioning the bus to pull over.

“Everybody stay calm; you’ve done nothing wrong,” Ross says, a reassuring but strict voice coming from the back of the bus.

“What’s going to happen?” a young voice inside the bus shouts.

“They are going to ask some questions — nobody answers but me.” Ross says, walking down the narrow rubber aisle inside the bus.

The center had hoped to bring a busload of adults and students on the trip, but the adults were fearful that, rightly or wrongly, the Border Patrol my have attempted to deport them. So, the trip was limited to students, all of whom have U.S. birth certificates. In fact, they brought them to the border, along with a volunteer immigration lawyer, just in case authorities got confused or overactive. The worry created by the crackdown has grown such that even immigrants with documentation are fearful of being snared.

As the kids shift in their seats, Ross meets a Border Patrol agent at the front, where she agrees to a search of the bus and for the luggage to be checked by eager German shepherds.

After being cleared by the Border Patrol and with a large puff from the brakes, the bus pulls back onto the dusty South Texas road.

Ross is in charge of the 52 West Dallas kids approaching McAllen. Wesley-Rankin is a community center in West Dallas that provides after-school programs offering help with homework, leadership skills and graduation preparation. Wesley-Rankin calls all of its students family, Ross says, and she set out on the 505-mile trip determined to teach the kids about Mexican-American history and introduce them to activists who could inspire them to speak out.

“These kids exist in a world that tells them they are second-class citizens, they are not loved and never enough,” Ross says. “Our message at Wesley-Rankin has to be louder than the world’s, and we have to pair this positive messaging with opportunities and a network to support the students along the way.”

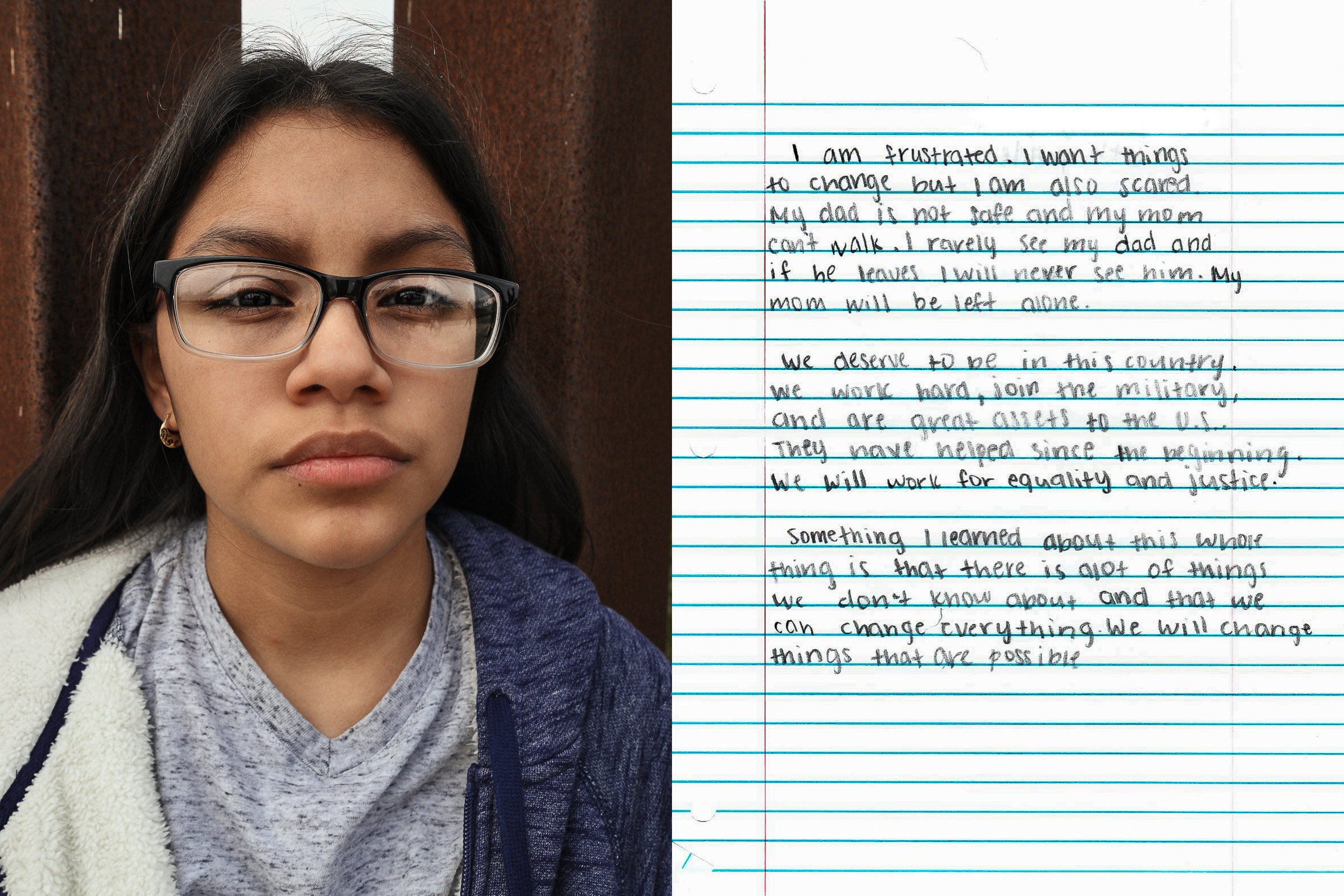

Although the middle- and high-school students aboard the bus reached the U.S. before the Trump administration ordered immigrant children to be separated from adult family members charged with crossing the border illegally, the Dallas students are familiar with the pain of seeing families split apart. Ally, a 19-year-old student, lives with her mother, and at times, she says, being with people outside of her school peers makes her “feel alone and without a sense of direction or purpose.”

“Being without the people that inspire me to do better and be better is disheartening, and with the recent targeting of my community, it makes me feel hopeless towards the future,” she says.

“Maybe this American Dream is only accessible to select individuals, no matter how hard I work.”

Like the other students, Ally believes that she can no longer be afraid to protest. Protesting might endanger her family's status in the U.S., but she believes using her voice will help shape the future for another Mexican-American like her.

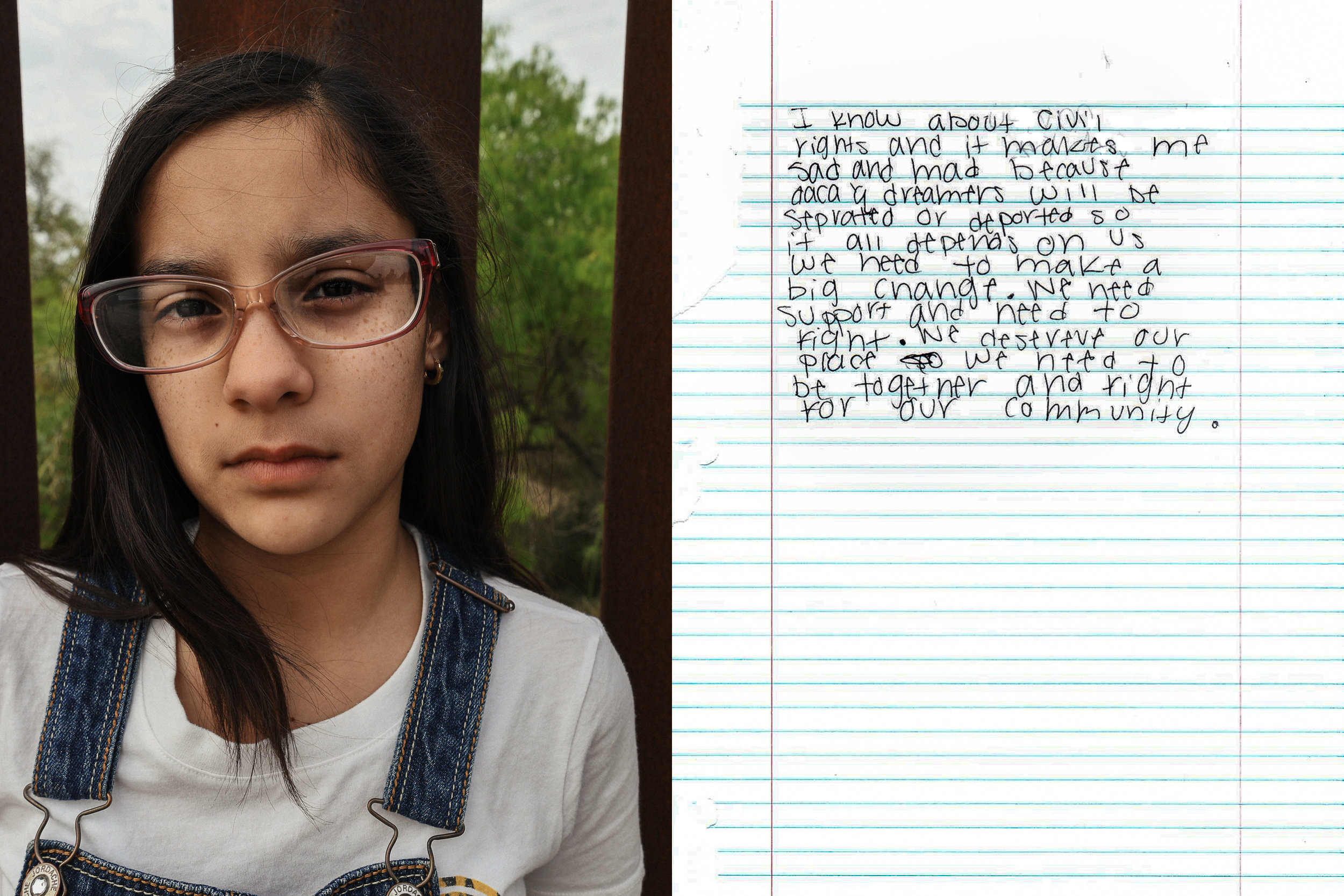

Gabrielle, a shy 17-year-old senior, joined the trip to become a voice for members of her extended family who remain in Mexico. She’s been afraid of public transportation since Trump’s election. She recalls the day she knew she had to join the trip in order to meet with other activists and learn how to stand up for herself. She was riding a bus home when a man stood up and began yelling that in Trump’s America, Mexicans will be sent back.

“I never want to be frozen with fear again,” Gabrielle says.

Gabrielle had just learned about the Mexican-American War and how a large chunk of what was once Mexico is now north of the border.

“I know now that the border crossed us,” she says. “I know that he was wrong.”

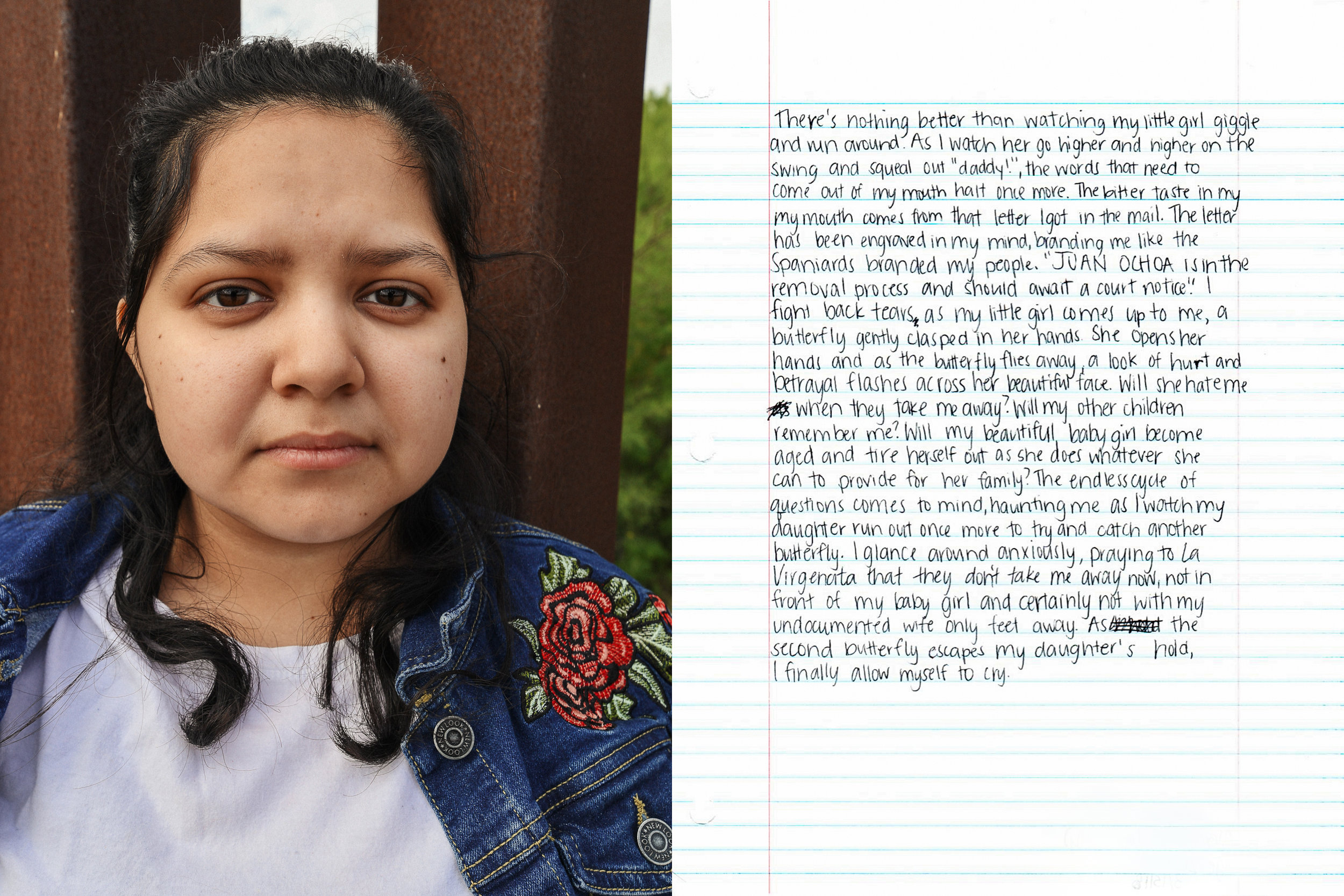

Carlos, a 16-year-old 10th-grader, says he has been avoiding school because he is worried authorities will find him there and take him away.

“I feel like I can’t say or do anything,” he says. “I want to protest, but I can’t do that because of my family, so I just have to sit here and take it.”

Carlos says he knows protesting is the right thing to do but that he feels more loyalty toward protecting his family.

“I just have to keep my head down,” he says.

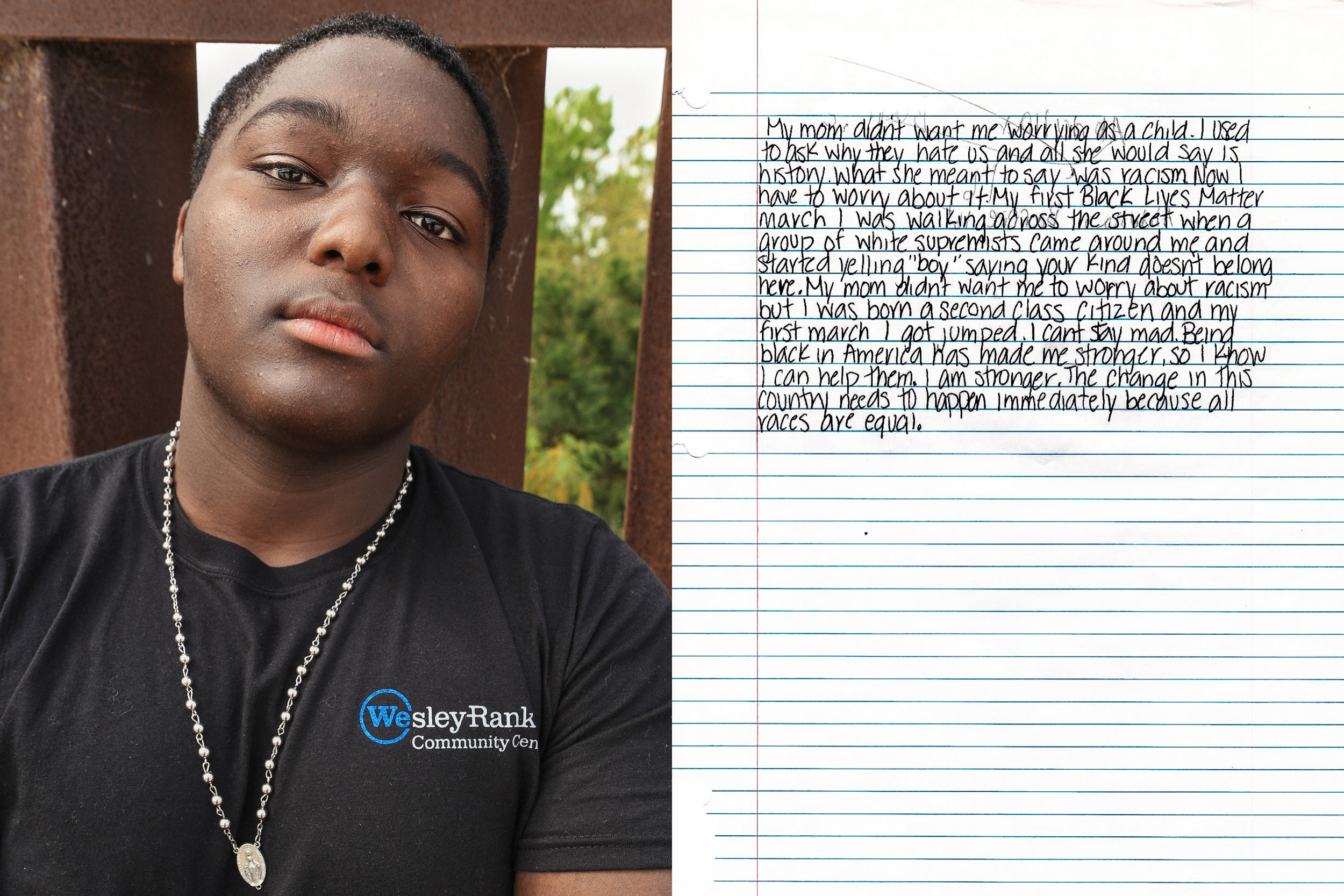

Abdullah, 16, is the only young black man aboard the bus. Tall and confident for his age, he says he was badly beaten by white people, whom he describes as supremacists, the first time he went to a Black Lives Matter march in Dallas.

“They all just came around me, you know?” Abdullah says, standing up to re-enact how he stood peacefully with his arms by his side, holding clenched fists. “I’m not going to walk away,” he says.

The students meet with Rosie Castro, a longtime Chicano activist and early member of La Raza Unida, a ’70s-era political group. (She's also the mother of former San Antonio Mayor Mayor Julian Castro and state Rep. Joaquin Castro.) They meet Jane Madrigal, a Chicano artist who painted the Chicano mural at San Antonio College.

“Everyone needs a hero, someone who looks like them, who has extraordinary courage to do the right thing even when difficult,” Ross says. “On this trip, our students meet heroes.”

They also meet with the former high school students who organized the Crystal City walkout in 1969. At the time, speaking Spanish in schools was prohibited. Chicanos were also being kept out of school activities. The school had a rule that only one position out of the four on the cheerleading squad could be held by a Mexican-American although the majority of the students were Latino. The Crystal City walkout was a watershed moment in the fight for Latino civil rights in Texas.

Severita Lara was 17 when she participated in the Crystal City walkout, and she urges the West Dallas students to “not worry about having babies or relationships so young — use these years to fight. People told us we were just kids, but you don’t have to wait. You can stand up for what is right now.”

Then the bus arrives in Hidalgo.

It stops at a completed section of the border wall that Trump has promised to extend along the nation's southern boundary. In Hidalgo, it looks more like a fence, its rusty brown vertical palings standing 21 feet tall, reminding one of the iron bars on a jail cell. Standing beside it takes the playfulness out of all the students. Some walk along the wall in silence, and others start to cry.

“Without my family, I have no one to talk to,” Ashley says. “This isn’t fair!”

Most of her family remains in Mexico. She lives with her mother.

“They will always discriminate against us. That’s what minorities are,” Cassandra says.

“It won’t get better,” Ashley says.

“They put us in cages. I am just so close — my family is right there,” Ally says as she points to the other side of the wall.

Ally wasn't put in a cage, but at the time of the trip, word has begun to spread of families being held in Immigration and Customs Enforcement detention centers.

“I cry every night,” she says.

Back in Dallas, the students have started to organize protests. They want more for their community, Ross says.

“The children have found a sense of purpose, and it’s beautiful,” she says.

With the mass incarceration and separation of families at the Texas border, the middle- and high-schoolers realize what they are fighting against.

“Life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness?” Ross says. “Not for our children. How can it be an American dream when it feels like a nightmare?”